Look at this abstract composition. Notice that all the shapes' edges are sharp. How our eyes move over the piece is determined more by location of shapes and their value contrast with their surroundings.

Let's change that up a bit and throw all the edges out of focus. Notice how you react to that--we want something to be in focus: Anything!

Now in this next design, pay attention to where your eyes go first. Do they migrate to that dark triangle on the right? The only shape that's in focus? I bet they do.

How do your eyes perceive this one with all but three shapes in focus? Scan backwards now and notice the difference in your response to each design. The shapes, colors, values and placement are the same. Only the handling of the edges is different.

Here's one more. How would you handle the edges in this one to make the design more pleasing to you?

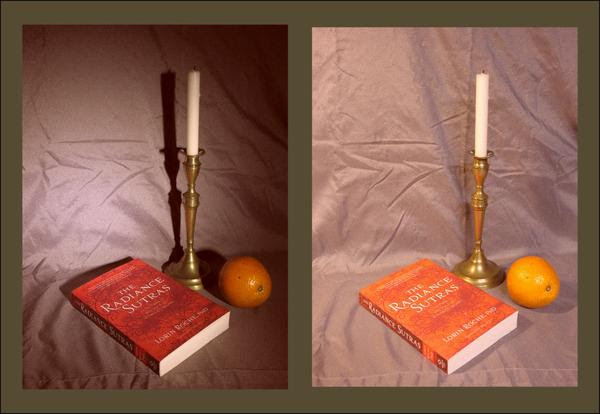

Whether our designs are realistic images or abstract, how we handle the edges of all our shapes will influence the perception of the total piece. All these examples play only with soft and sharp edges. Other choices are broken, jazzed, lost, gradated--possibilities are limited only to the imagination. What's important is that we notice what we are doing and find ways to use edges to strengthen our compositions.