Do I detect an elephant in the room?

This week's post will be a bit different, sort of a side bar, because I want to air something that's been on my mind for a long time. Why do so many artists resist compositional principles?

I've noticed it especially on the Wet Canvas forums, I'm bumped into it quite often on the blogs and I've surely encountered it eye to eye with other artists. It appears that many artists think of compositional or design principles as rules and therefore resist them.

I googled "compositional principles" and the garbly-gook that resulted could clutter ones brain. As I was plowing through these sites, one by one, I had an ah-ha moment: this stuff isn't accessible. It's rhetoric, it's jargon, and it's brilliantly obscure. Face it, what we've had crammed down our throats all our lives is something that's totally meaningless for us while we're pushing a brush. For example, what does this mean: "

rhythm and repetition act as agents for creating order out of forces that are otherwise in oppositions."

Now get this. I taught this stuff in college and I didn't feel comfortable with it then either. I've battled for years trying to find ways to make compositional principles attractive to students. I went about it all wrong and now I know why:

if it cannot work for me while I'm painting, it's no good to me.And there within the word

work lies the clue that solves my mystery.

All these many ions artists have been taught that design principles are rules. BUT, that doesn't work because we hate rules. We'll not be governed by any rule and besides, rules restrict our creativity. Am I right?

Second, the way this stuff has historically been presented to us is

inaccessible to us. Sounds good but to what end. Am I right again? And maybe we don't want to confess we don't really understand those dense assemblies of words found in our design manuals. That would be unacceptable, make us appear intellectually inferior to the critics and historians and those New York mainstreamers. (Mmmm. I won't ask you to confess this one.)

Okay artists, listen up:

not a single principle is a rule. NOT ONE.

Every single one of them is a

tool. There's a wide world of difference between a rule and a tool. The only thing they have in common is cause-and-effect.

- Rule: if I get caught breaking the speed limit, I'll pay a fine. A rule governs my behavoir (or not).

- Tool: if I apply the pedal to the metal, the car will go faster. A tool enables me to accomplish something (or not).

As artists we make observations every day. We know if we mix one color into another, we'll get a new color. That's a

tool, not a rule. We know that if we put a quarter in a piggy bank, we'll have it as long as it stays there. That's a

tool, not a rule. We know that if a single dark spot it placed on a white canvas, our eyes will go to that spot. Again, a

tool, not a rule.

If we take every single design "principle" we've ever encountered and re-think it as something that can be a workhorse, we will discover we have a huge box of tools. HUGE. Are you getting my drift? Anything we can use to make our work do what we want it to do is a

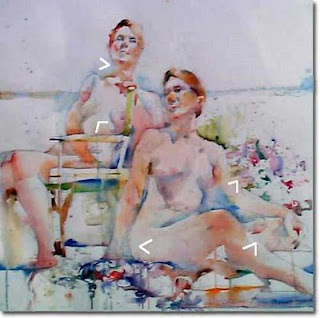

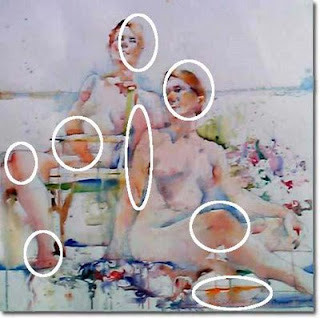

tool.When we looking at a painting by

Richard Schmid, what we know immediately is Schmid works those tools. Look at one of my favorite Schmid paintings "Yorkshire Coach House."

Schmid has worked with each of the tools for so many years that he reaches for one when he needs it and, immediately, it goes to work for him. I know for certain that he learned how to use color by doing charts. I'm betting he has done his fair share of practicing every tool he uses.

We can move from one accomplished artist to another to find that the one thing they all have in common is they can utilize the tools.

And it's never too late to take one tool at a time and practice using it just like we'd practice using a chain saw. We'll be a bit awkward at first, but the more we practice using it, the easier it will become to keep it working for us whenever we need it, to make it do for us whatever we want it to do.

In these blog entries and in

my articles for Empty Easel, it is my goal to show you ways you can practice using these tools so that for you, they can become workhorses, not threatening rules. Leave me a message if there are tools you'd like me to address.