Paint by Jackson Pollock "Number 8"

Paint by Jackson Pollock "Number 8" Couples Figure Skating--Photo from mahalo.com

Couples Figure Skating--Photo from mahalo.comI can remember many years ago a certain figure skater whose routine was not much more than a set of circles with a flying bird body formation. I thought it was quite boring at the time, but we don't see any of that these days. No indeed. Figure skating can be heart-stopping with the many multi-directional changes and leaps.

Likewise, I notice that paintings with a strong directional dynamic hold my attention much longer than those whose movement is too quiet and static. Movement is the key word here: we use the visual element direction to create visual movement. Visual movement creates visual paths. And the nature of movement can create rhythm. So a lot rides on how we use direction as a part of our visual language.

We all know what direction is. North, south, east, west, right, left, up, down, around and around--all those points to which we are constantly aiming and switching. You can't even get out of bed in the mornings without changing direction. And we use "changing direction" as a life metaphor, business metaphor, relationship metaphor, behavior metaphor.

It's role in our painting? To control the viewer's attention. That sounds pretty important, right? Okay, so what do we have available to work with. Well, we can use horizontals (right and left), verticals (up and down), diagonals (leaning), and circles ('round and 'round and 'round and 'round). The key is to use these with enough repetition to prevent chaos and enough variation to keep the viewer engaged.

So how do we create with direction? Flow and transition. Two masters come to mind: Charles Reid and Richard Schmid.

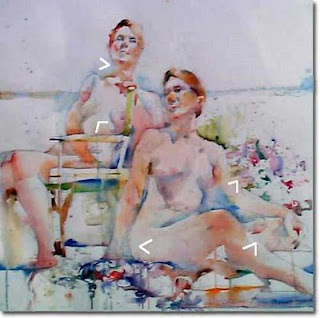

1. Accenting points

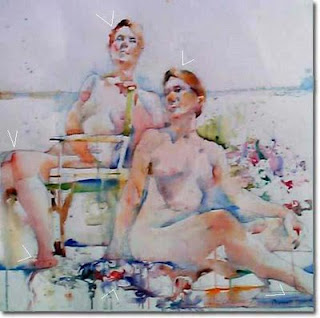

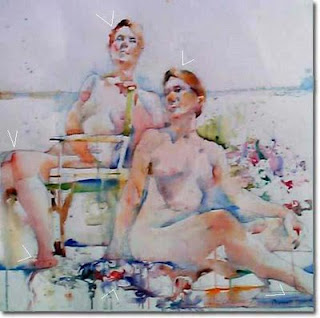

Charles is adroit at accenting certain points of the total composition so that our eyes want to move --make a transition--from one area to another.

I've indicated some of the major ones with little white arrows. Keep looking--you'll find more

2. Losing edges

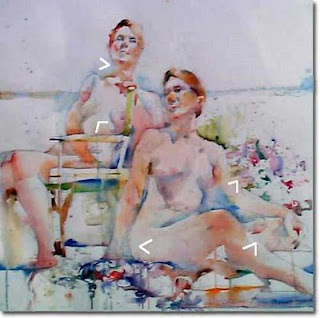

Charles is also adroit at utilizing lost edges, another tool that enables the eye movement to flow and to transition from one area to another.

Again, I've used little white arrows to point out a few key areas. Keep looking, though, and you'll keep finding them.

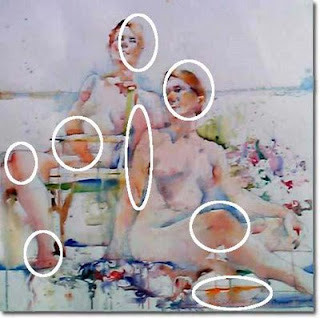

3. Repeating Color

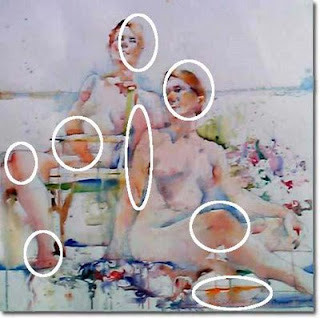

And another of Charles' real genius is his inate ability to repeat color while giving it just enough variation to keep it from being boring. I've circled a few examples here.

These repetitions of color also act both to create flow as well as make transitions.

In a cool background, Charles has used the repetition of warm colors not only to define skin tones and hair, but also to keep the eye moving in various directions.

Next we go to Richard Schmid.

Likewise, I notice that paintings with a strong directional dynamic hold my attention much longer than those whose movement is too quiet and static. Movement is the key word here: we use the visual element direction to create visual movement. Visual movement creates visual paths. And the nature of movement can create rhythm. So a lot rides on how we use direction as a part of our visual language.

We all know what direction is. North, south, east, west, right, left, up, down, around and around--all those points to which we are constantly aiming and switching. You can't even get out of bed in the mornings without changing direction. And we use "changing direction" as a life metaphor, business metaphor, relationship metaphor, behavior metaphor.

It's role in our painting? To control the viewer's attention. That sounds pretty important, right? Okay, so what do we have available to work with. Well, we can use horizontals (right and left), verticals (up and down), diagonals (leaning), and circles ('round and 'round and 'round and 'round). The key is to use these with enough repetition to prevent chaos and enough variation to keep the viewer engaged.

So how do we create with direction? Flow and transition. Two masters come to mind: Charles Reid and Richard Schmid.

1. Accenting points

Charles is adroit at accenting certain points of the total composition so that our eyes want to move --make a transition--from one area to another.

I've indicated some of the major ones with little white arrows. Keep looking--you'll find more

2. Losing edges

Charles is also adroit at utilizing lost edges, another tool that enables the eye movement to flow and to transition from one area to another.

Again, I've used little white arrows to point out a few key areas. Keep looking, though, and you'll keep finding them.

3. Repeating Color

And another of Charles' real genius is his inate ability to repeat color while giving it just enough variation to keep it from being boring. I've circled a few examples here.

These repetitions of color also act both to create flow as well as make transitions.

In a cool background, Charles has used the repetition of warm colors not only to define skin tones and hair, but also to keep the eye moving in various directions.

Next we go to Richard Schmid.

Richard's delicious brushstrokes are to my mind his trademark genius. Each stroke is guided with intention to define whatever subject is being painted using the careful placement and movement of the stroke.

5. Giving Attention to Edges

Where Charles can lose an edge, Richard can manuver it along the perimenter of the shape to show roughness or smootheness, softness or hardness, swiftness or slowness. His edges are not just perimeters--they control eye movement.

Edges contain characteristics that define the subject. Richard finds these characteristics and renders them in a way that the eye wants to pause and taste it before moving on to the next area.

Edges contain characteristics that define the subject. Richard finds these characteristics and renders them in a way that the eye wants to pause and taste it before moving on to the next area.

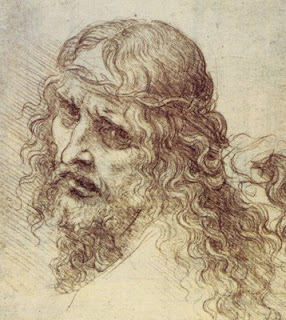

But perhaps the all time great master of using direction was Leonardo da Vinci. With every thing he did in a painting, he was manipulating our attention just as with every note, volumn and rhythm, Mozart was doing the same thing.

6. Positioning Your Subject

Leonardo turns the face of the Christ-figure toward the left edge, then shifts the eyes to look at the viewer while directing the flow of the hair down the shoulder to the right-hand corner.

Leonardo turns the face of the Christ-figure toward the left edge, then shifts the eyes to look at the viewer while directing the flow of the hair down the shoulder to the right-hand corner.

He uses a similar ploy in his world-and-ages famous Mona Lisa where the eyes are looking at the viewer, the face is turned slightly toward the left and the hands are positioned toward the right.

Throughout time, where genius has come into play is the artists uncanny ability to notice what's available and to use it adroitly. So we're right back to last week's lesson and all those before. We hone our skills and our eyes and join them together to make it work.

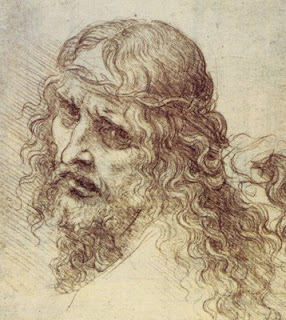

6. Positioning Your Subject

Leonardo turns the face of the Christ-figure toward the left edge, then shifts the eyes to look at the viewer while directing the flow of the hair down the shoulder to the right-hand corner.

Leonardo turns the face of the Christ-figure toward the left edge, then shifts the eyes to look at the viewer while directing the flow of the hair down the shoulder to the right-hand corner.He uses a similar ploy in his world-and-ages famous Mona Lisa where the eyes are looking at the viewer, the face is turned slightly toward the left and the hands are positioned toward the right.

Throughout time, where genius has come into play is the artists uncanny ability to notice what's available and to use it adroitly. So we're right back to last week's lesson and all those before. We hone our skills and our eyes and join them together to make it work.