American painter Richard Schmid has an intuitive eye for design. Those of us who know Richard's work never tire of viewing the same painting every day of our lives, no matter which one it is. What is that quality in a master artist?

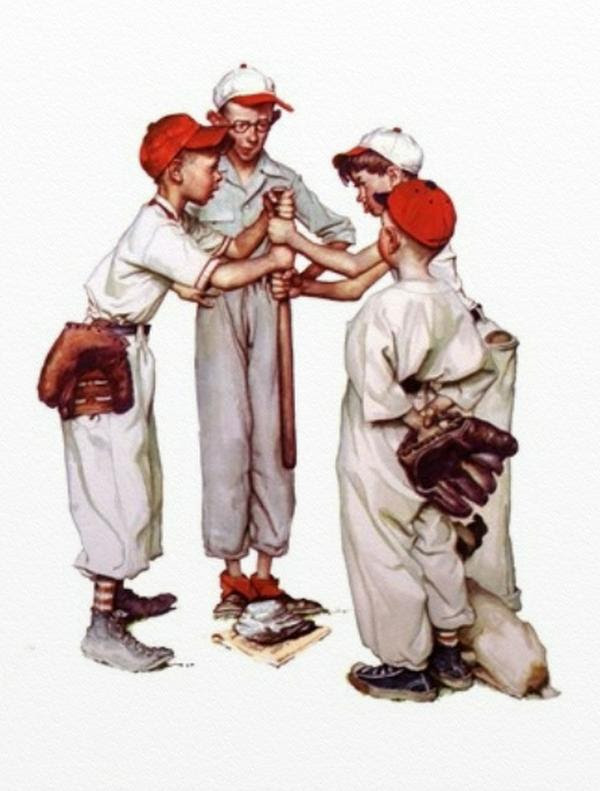

Take the painting above, for example. It's more than just beautiful, although beauty is undeniably present. It's not just technique even though Schmid is a technical master, but so are others whose work can seem lifeless. Neither is it his decades of training and experience. It's much more and I think Schmid himself gives us a few clues in his own words.

From his book, Alla Prima II, he says this to his readers:

"When choosing your subjects, never worry about greatness or significance or your place in history. Let your subject come from within you and be an honest act of sharing."

Later on he says:

"You are the sum of your choices. Your job then is to make sure your ideas about what to paint are not wholly based upon either the acceptable or the taboo, but arise instead from what honestly fascinates and stirs you....your task is to get in touch with yourself. Find out what moves you, what you believe in, and what you truly understand about life."

Perhaps THAT's why Richard's paintings always sing. They come from his authentic voice.