Does every painting need a focal point? Not always, say some professionals, but others consider it an absolute requirement. In fact, many artists take focal points for granted, including them in a composition without thought for whether or not a successful painting might need such a thing. So what is a focal point and why do we use it?

Also called a center of interest, a focal point is the area of emphasis around which the rest of a painting is centered or something in strong contrast that pulls the viewer's eye into the painting. But sometimes an artist will have other intentions and abandon the focal point altogether

We’re all familiar with the work of action painter, Jackson Pollock. Because of the nature of his painting process—distributing drips and splashes with repeated movement throughout the canvas—Pollock’s later work does not have a focal point. Instead, we are engaged by the endless maze of paint, a pattern created by movement such as we see in his Number 8, 1949.

A different kind of intention—that of repeating a single image with variations set in a tic-tac-toe grid—is found in Andy Warhol’s Marilyn, another work where there is ot really a focal point.

Non-objective painter Piet Mondrian arranged and repeated squares and rectangles into compositions that leave us in question of whether there is a focal point. In Broadway Boogie Woogie, below, there seems to be a focal point in the upper right quadrant of his painting—the yellow rectangle inside the red square, sandwiched on top and bottom by the blue rectangles--but we are left in question.

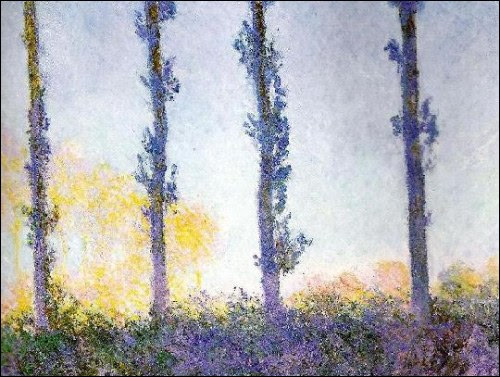

So far our examples have been from historical masters of various abstract movements, so do we conclude that only in more conceptual painting does the focal point not apply? Not so quick: our Impressionist hero, Claude Monet, did a little focal point deleting himself. Take a look at his painting, Poplar Trees.

The alternation of trees and sky in this painting make the entire piece the focus. We see then that the question of focal point has nothing to do with whether a painting is non-objective or realistic, but whether the images are ordered so that every inch of the painting is important to the whole.